Sigrid Lien

Professor of Art History at Bergen University

Ten years ago, I received the gift of a beautiful woodcut. The print was signed Rita Marhaug (then an art student), and the motif was well known from art history: three graces—voluptuous, dancing female figures. In the foreground of the picture there lay a nude sleeping man. […]

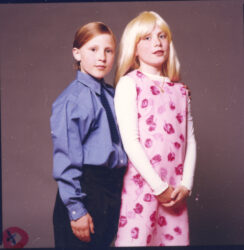

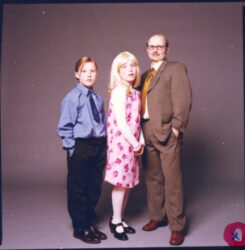

Ten year later, a morning in May 1999, I found myself an observer to a piece of performance art by Rita Marhaug. In the course of a few hours the artist recreated herself into a short and bald man. After fully disrobing, she carefully clothed herself in male attire: jockstrap, male underwear and brownish-grey business suit. Gradually the masculine attributes fell into place: a neutral tie, correct glasses, sideburns, a discrete moustache (made of the artist’s own hair) and finally—a slick of hair pulled over from the side to camouflage the balder crown. The artist’s children, Kaspar and Sofie, changed sex as well. The girl became a boy, the boy became a girl and the traditional family portraits were taken. Marhaug herself displayed great ironic familiarity with typical male gestures as she posed assuredly: her weight equally distributed on both legs with an air of self-importance. The art work, simply entitled (Portrait of the Artist) as Small Man at the Photographer, was fully recorded on video and with photo documentation of all its phases.

The leap from aesthetically delicate graphic print of the mythological figures to this performance seems at first glance not only long but also unexplainable. Why does the artist transverse such wide specter of expressions? Is it at all possible to find any common themes in the production of Rita Marhaug?

I sense there is a connection between the works just mentioned. In an attempt to elaborate on this, I refer to the Danish art historian Simon Sheikh, who has pointed out some of the more marked tendencies in contemporary art. According to Sheikh, art of the 1990’s shows more than just a new style of freedom: what he characterizes as freedom from form and media specific, object-oriented artistic production. It also had another noticeably characteristic feature. It concerns itself with what Sheikh calls “the social”. He defines this social theme more closely as “…daily practices and all they entail, what they contain of social drama, boredom, coincidence and physical bodily function, not least the playing of social roles, both within and outside the sphere of art”. Hence Sheikh sees that the division between art and life which among others Robert Rauschenberg attempted to bridge at the beginning of the 1960’s, has now been absorbed into the life of the artist, showing itself as artistic practice where the artist’s artwork is the practice of their life. This also means that interest in the role of the artist or the artist as an actor has increased.

The features Sheikh points out here seem apparent in Marhaug’s art. She has first of all an aesthetic sureness and the proficiency of craft belonging to a professional artisan which enables here to move freely from one genre and media to another, all the while challenging accepted attitudes about the autonomous nature of a work of art ant the aura accompanying it. Secondly, critical reflection arises over the identity and role of the artist with all its mythologies. Aspects of power pertaining to gender provide a kind of driving force in the whole of her art. Marhaug’s own tale about her first meeting with what she experienced as male fellow students sexually political cultivation of Duchamp is in itself an indication of this:

“[…] Later as an art student, I observed a group of male students who for a whole semester enthusiastically played chess at school. As young artist they had found a figure to identify themselves with; Duchamp. In particular I think of his performance – the artist playing chess with an anonymous unclothed woman. These same students are today actively engaged in “the young artist” movement in Norway and Scandinavia. Here the Duchampian strategy is an important part of the theoretical foundation for the understanding of art and the artist’s role.”

Marhaug is painfully aware of the resilient romantic myth of the artist, its ideological premises and pragmatic consequences. To act freely from the conventions of social demand that artists make themselves noticed in the public sphere. Again, visibility and fame have always been prerequisites for achieving economic benefits and social privileges. In connection with this, Marhaug refers to the American cultural sociologist Leo Braudy, who shows that pictorial artists from the renaissance onward have not only taken pains to visualize the cultural reputation of their patrons. They have also positioned themselves through their work. Above all else the self-portrait can be seen as a step in the marketing of an artist. Here gender and the aspect of power are both apparent. For Marhaug, the two self-portraits of male artists Gustav Courbet and Jeff Koons, L’Atelier du Peintre (1855) and Made in Heaven (1989) represent classic examples of how romantic male artists of the modern era respectively present themselves as the potently masculine cultural power (in contrast to the traditionally passive female) and as a conceptually able, narcissistic seducer of the masses.

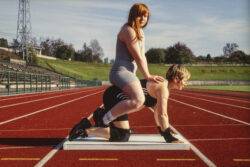

With this as a backdrop Marhaug undertakes her alternative staging of the artist subject. She uses herself and her own body in these productions, keeping humoristic distance from the myth of the artist. And she combines, in line with Sheikh’s observation, experiments of roll playing with other forms of life practices than those traditionally within the sphere of art. Among other things, she draws upon her experience within her family and as a participant in physically demanding sports. In a series of photographs, she challenges the traditional understanding of the artist identity by posing in the gear of a weight lifter, kneeling on all four, with one or more of her children on her back. The titles of the photographs are in themselves a comment on the problem of identity: of these “self-portraits” one carries the title 33 + 11 years, another 120 kilos (265 pounds). A whole specter of roles stereotypes is utilized as raw material for her identity projects […].

In Knock Out, the so called “hard hitting artist” entered the scene. After months of intensive boxing lessons Rita Marhaug entered one of the salons of Bergen kunsthall where, with her ritual thoroughness, she wrapped her hands in protective bandages, put on the boxing gloves and began punching. First, she did a regular warm up with a punching bag, then with heighten ignition and tempo she let loose on the public. Sweat poured and her temper glowed as she physically challenged the experience- seeking company. Soon enough the public withdrew in surprise and distaste. This female artist, the provocateur, was left standing, infinitely alone in her enthusiasm—and with her eventually so very melancholy and meaningless punches into thin air! This same form of furtive irony forms the basis of her pseudo-biographical presentations of The Small Man, for that which is shown is nothing other than the small man (and there are many of them, both within and outside the institution of art) who square and plump acts as the self-appointed and self- important center of his little universe.

The masquerade is thus a central theme of her artistic practice, which paradoxically results in her work being seen as related to the aesthetic of Marcel Duchamp. Yet they refer to another aspect of his work than those which have apparently given him status as the academy idol. Duchamp’s photographic masquerades from the 1920’s where he appears as the woman, Rrose Sélavy and Belle Haleine, challenges not only the understanding of identity implicit in traditional portraiture. Just like Marhaug’s later experiments in identity, the masquerade can be seen as a fascination over gender construction mechanisms and the field of tension surrounding androgyny.

Yet the widely oriented Rita Marhaug has several points of reference for her activity. One of these is the British performance couple Gilbert and George who early on challenged art’s pretensions of immortality. In a playful, anarchistic way they recreated their own bodies into objects of art: works which cease to exist the moment the performance ends. This set of problems is carried further by another of Marhaug’s precursors, the female artist Orlan.

Orlan has turned her attention to the role of the woman as a pictorial object in art. Through a series of plastic surgery operations started at the beginning of the 1990’s she transforms her own subject into a picture which synthesizes the woman of Leonardo, Raphael, Boucher and Botticelli. Rita Marhaug is concerned with the questions the transformed face of Orlan raises: what is here which constitutes the actual work? And to what degree is the artist breaking with the traditional conception of the permanence of work of art?

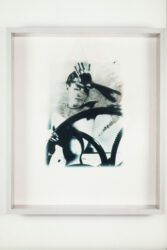

According to Marhaug the break is only apparent. The pretension of permanence—the wish to ensure the life of the art work after the artist’s bodily death—is found among other things in the production of what she calls relics: the creation of theories, videos and photographs. She also produces such relics. Being too much of an aesthete to turn away completely from the materiality and formal aspects of an art work shows not only conceptual fantasy, but also great sensual joy in all she does as a pictorial artist. One of the many examples of this is her pictorial series I.D. (1997-98) where she allegorically combines photographs from antique sculptures (the Doryphoros by Polykleitos and an archaic sculpture of a woman) with photos of her own unclothed body. The meshing together of these components becomes pictures with mystical transparencies: a meeting between the past and the present, between the male and the female body and between the body as sculpture and the sculpture as body. This allegorical method of combining can also be found in Rita Marhaug’s later work. The use of it opens, as she says, an opportunity for showing respect and enjoyment of past artists and their work. In three large graphic prints she lauds the Baroque painter Velazquez, whose position in art history rests precisely on his mythological parodies and mysterious staging—and also reflects the position of the artist. In these prints Marhaug literally puts together Velazquez court portraits of the prince, the princess and a dwarf, together with photographic portraits of her son, her daughter and herself.

Another of those to whom she shows respect is Meret Oppenheim. Her point of origin here is Man Ray’s highly staged photographs of the female surrealist artist […]. In an additional declaration of homage Marhaug creates her own version of Oppenheim’s most famous work: Le Dejeuner en Fourure—the fur covered cup from 1936. Marhaug’s version in skin colored leather seems to continue to play on the bodily, sexual character witch already exists in Oppenheim’s suggestive coupling of hair and liquid.

A third example of Marhaug’s historical and allegorical compilations, are two hand-crafted and self-produced books: Songs of Experience and Songs of Innocence, where she weaves together texts of William Blake and the American grunge rock band Nirvana. In other words, it is the male romantic poets she quotes and combines into a new work, signed Marhaug. Hence, she signals a kind of ambivalence to the myth of the romantic visionary artist. We viewers cannot be exactly sure where we have her. As the three graces in the picture of the sleeping man, she veritably dances around us. All the while she holds us locked—in a playful ironic, aesthetic, poetic and ambiguous grasp.

ــــــ

https://www.ritamarhaug.com/uploads/2/3/3/3/23330060/art_life_roles_and_relics.pdf

Projects

Projects  Art, Life, Roles and Relics: Some Reflections Concerning the Visual Art of Rita Marhaug

Art, Life, Roles and Relics: Some Reflections Concerning the Visual Art of Rita Marhaug