Soft Life

Rita Marhaug, in response to the question “But what is your profile – do you want to work with image or concept?” explains:

Maybe this question is still relevant for others. My own perspective has taken another direction. Seduction, masking and de-masking are amongst the elements that I value today: that the audience can be simultaneously attracted and repulsed. I value also the contrast between our sense of sight and touch – not least how vision requires distance, where touch demands absolute closeness. This has been central to my work with live animals and with fur as a material.

The union of paradoxes was the aim of many of the Surrealists, with the belief that juxtaposition would lead to a higher, harmonious unity. I can identify with this–not the belief in harmony, but rather the need to find a form for the acceptance of oppositions. Within opposition lies the inherent dynamic between life and death, predator and prey: the one is reliant upon the other.

Meret Oppenheim’s Le Déjeuner en fourrure, a title given by André Breton is an artwork I have continued to return to. This modestly sized sculpture–or object–the fur cup of 1936, was a defining moment for surrealism: but also, for the emerging group of artists that raised a whole other set of problems–women.

I had the pleasure of seeing Oppenheim’s work in Berlin in 2013, when Martin Gropiusbau showed it in a retrospective of Meret Oppenheim. During the residency, I bought as planned a roll of thin, skin-like textile fabric. This material–together with the different qualities of fur, silk, felt and animal skins, is one that I have returned to in various ways. This fabric has grown in size to over 200m2, performing as a wall or central object in both interior and exterior settings. Through fur and skin, I have sought out the fantasies of childhood and tactile desires.

Surrealism and childhood–both portals to the irrational–a third inspiration is the Baroque. Manipulation and seduction, the Counter Reformation’s and the autocrat’s propaganda apparatus, became distrusted in the 20th Century and under Modernism. The philosopher Gilles Deleuze has pointed out the epoch’s insights and how it can be traced back to Antique philosophy and aesthetics in the essay Le Pli. Leibniz et le Baroque. His interpretation of Baroque metaphor opens the door to a closed period.

The philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin discusses Baroque thinking in The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Benjamin looks closely at popular religious plays and power structures of the 17th Century, comparing them to the trauma of the 1st World War. According to him, tragedy belongs to the Antique, whereas grief belongs to the Baroque: a period that was concerned with melancholy and depression. Benjamin highlights these aspects within his own time. Almost 100 years later, it is possible to register these as strong tendencies in our own welfare society.

Covering and uncovering, trickery and suggestion–things that work directly upon our feelings is a phenomenon that we now connect to low and mass culture: preachers, circus and reality-TV. In recent years, certain TV series have achieved wide spread recognition through streaming services, and have been embraced by academia as ‘the new novel.’ As in the Baroque, we are manipulated and tricked with actions and situations that happen in the shadows, only ever partially illuminated by the work of the grudging police detective Sarah Lund.

Above even the visual, TV gives time to the viewer, where perspective can be twisted and turned with both soft and hard methods. Lingering on – and titillation of – the sensory, so central in this format, is also a tool of the Baroque. As a viewer, one becomes engaged and drawn into speculation about how the narrative will develop. Our attention alternates between small details and overarching storylines.

The connection between past and present, high and low culture is what inspires the development of my work. The latent ambivalence between repulsion and attraction is what drives many of my visual experiments. Surprise also has its place here. Through work with small details and short performed actions, the spectator can choose to focus on fragments rather than the whole – or follow a longer progression of action such as in Fernanda Chieco’s exhibition project The Cell, where I was engaged in a 29-hour performative process with actions and shifting constellations of objects in a room of 5 square meters, with large windows in Bergen Centre. In this way, coincidental passersby could follow the events on their way to and from other business.

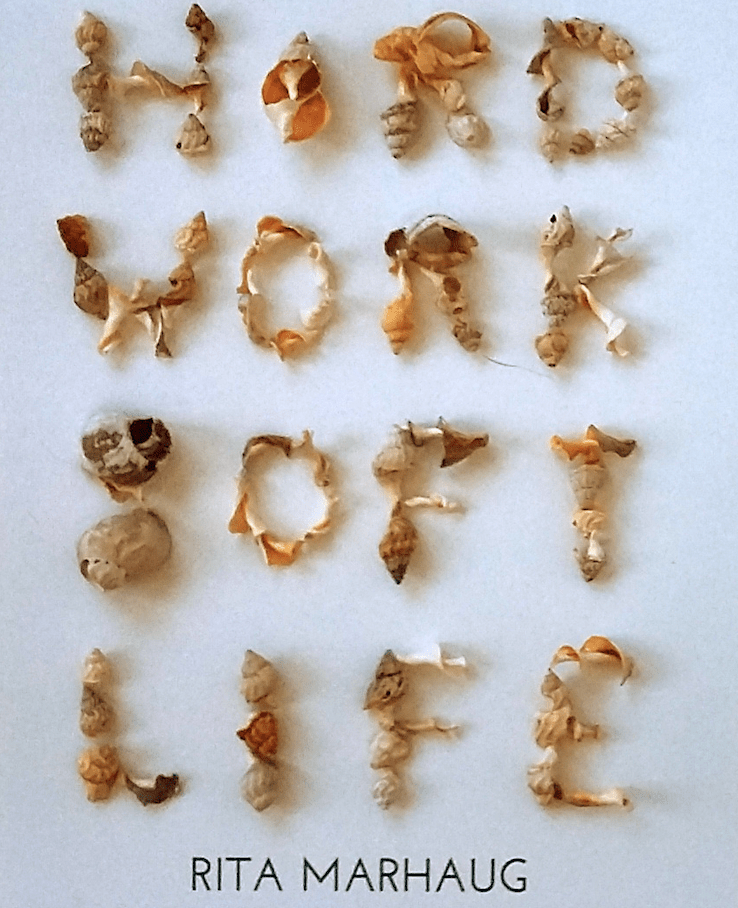

Hard Work

Visual actions between material and body characterize my methodology of the last decade. This can also be seen as converging with the art world’s renewed interest in material-based techniques. In 2016, I showed an installation called Predator at Pink Cube in Oslo. The main elements were black Persian lamb fur (which comes from the newborn lambs of karakul sheep) and black oil, mounted in folds across the entire surface of the gallery’s back wall. On the opening night, there was also a transformative performance. From a kind of sleeping bag or cocoon, made of the same material, placed on the floor in front of the opposite wall, my character came creeping out amongst the audience. The figure had a black hood that entirely covered the head, and an otherwise transparent, beige costume. Oil began to run out of the hands and feet through hoses attached to the mask. The figure moved through the room towards the fur wall, where it triggered a mechanism that caused the wall to ‘bleed’ black oil. The liquid crept slowly out across the floor, whilst the character left the gallery. The audience trod in the oil spillage, and by the end of the night, all the floors were ‘infected.’ Predator and prey are two terms that have led my working process to different projects. The wild and the tame, dominance and submission are important oppositions in the development of several tableaux, amongst them the photo series Predator. In our culture, the lamb as an image of sacrifice, but also of savior, is a clear contrast to mankind and its best friend the dog.

This tactile track is developed and pursued in the next works within a beach landscape, using natural elements found in this context such as seaweed, kelp and shells. The snail shell is a familiar motif in the classical tradition. In the Baroque, the spiral can be understood as an image of continuity, cyclical time, spiritual growth and mystery. In older still lives, conches and oysters are often depicted as a memento mori. The shiny, smooth mother of pearl that forms the shells’ opening and insides has a similarity to female sexual organs. Simultaneously, the opened shells are nothing more than the skeletons of the molluscs that once lived inside them. The exhibition TIDE at Christinegård gallery in the summer of 2018 presented an installation that included 14 kilos of whelk shells. A body analysis showed that this was the same weight as my skeleton. The visual balance of inner and outer mass, life and death are once again juxtaposed.

In the performance Trust Me at PAB Open in 2017, Chibs the St Bernard dog and my character spent a whole day together. With an ox’s thigh bone, power and trust was given and taken in an apparently rosy atmosphere, in front of a tense audience. As mentioned, in Personas at Atelier Chieco, the audience were able to observe details in the interaction between human and dog, or regularly pass by the room and follow how the sunlight changed the composition of the pink drapery throughout the day, or how the animal slowly and surely consumed the bone and simultaneously ‘polluted’ the surroundings with drool and splinters of bone, and of course the intense ‘dog smell’ which had entirely filled the room by the end of the day.

ـــــــــــــ

Marhaug, Rita. “Hard Work, Saft Life.” In Hard Work, Soft Life, edited by Rita Marhaug, 14–43. Bergen: PABlish, 2020.

Projects

Projects  Hard Work, Soft Life

Hard Work, Soft Life